Studying Mental Health in a Developing Country

Leyla Ismayilova finds family counseling with economic intervention reduces maltreatment of children in Burkina Faso

By William Harms

VOLUME 24 | ISSUE 1 | WINTER 2017

Exposure to violence, deprivation, and other adverse childhood experiences affect multiple mental health outcomes among children with effects that are often long lasting. SSA Assistant Professor Leyla Ismayilova shows in new research in the western African country of Burkina Faso how those conditions affect children's emotional well-being and how a program to intervene has brought significant improvements, including an important reduction in abusive family environment and children’s reports of depression.

ABSTRACT

Assistant Professor Leyla Ismayilova studies child maltreatment in one of the world's poorest nations, Burkina Faso, in western Africa. Her work shows how family counseling can improve the lives of children, who experience emotional and physical violence and who often work away from home to help support their families. She studies how the counseling can be combined with an economic project that helps raise incomes for the very poor. Hers is among the first experimental design to test the impact of integrated psychosocial and economic-empowerment interventions on the child protection and mental health outcomes among families in very poor countries. Her work shows the combined intervention led to a reduction of hunger among children as well as lower symptoms of depression and trauma. Mothers who participated in the combined intervention showed reduced use of harsh discipline methods.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

"Harsh or non-supportive parenting practices, often highly prevalent among families living in adverse circumstances and chronic stress associated with family-level poverty, can even further undermine children's psychosocial functioning and weaken children's abilities to adapt and deal with trauma," she says.

Children in Burkina Faso, one of the 48 Least Developed Countries, are particularly vulnerable to exploitation. Burkina Faso has one of the highest rates of child labor in the world and a 2012 survey found that 1.25 million or 37.8 percent of children ages 5-14 in Burkina Faso were working to augment the incomes of their families.

In addition to stressors outside of home, Ismayilova's article recently published in PLOS ONE has shown that almost half of the child participants (44 percent) in Burkina Faso experienced physical violence and 58 percent reported emotional violence at home, including when parents were shaming children by making them stand on their knees or depriving them of food as punishment. Such exposure to violence in the family was among the strongest factors connected to poor mental health among these children, including increased symptoms of depression, higher symptoms of trauma, and lower self-esteem.

Although relationships between stress brought on by poverty and mental health have been well-documented, practitioners in developing nations still lack effective, culturally appropriate and low-cost intervention tools that could strengthen the way families can deal effectively with the stress, she says.

> > > . < < <

The path to social work was an unusual one for Ismayilova, who grew up in Baku, the capital of the Azerbaijan, a republic in the Caucasus region of the former Soviet Union.

She received a bachelor of science degree in psychology from Baku State University, was trained in group psychotherapy at the Central Clinical Hospital in Baku, and received a master’s degree in psychology from Baku State University.

The path to social work was an unusual one for Ismayilova, who grew up in Baku, the capital of the Azerbaijan, a republic in the Caucasus region of the former Soviet Union.

She received a bachelor of science degree in psychology from Baku State University, was trained in group psychotherapy at the Central Clinical Hospital in Baku, and received a master’s degree in psychology from Baku State University.

While she was pursuing her doctoral degree, she learned of an opportunity to study social work at Columbia University and decided to pursue it. "I didn’t know what social work was. In the late 1990s, we didn't have a profession like that in Azerbaijan or anywhere in the Soviet Union. But the description sounded like what I did as a psychologist, so I applied,” she says. Ismayilova was among the first Social Work fellows brought by the Open Society Foundation (Soros Foundation) from six former Soviet Union countries (Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan) and Mongolia to study social work at American Universities, specifically at Columbia University and Washington University in St. Louis. Since then the program has trained a cohort of social work professionals who have returned to their home countries and became instrumental in setting up social work bachelor’s and master’s degree programs at local universities and establishing local professional associations of social workers. "Being a part of this process showed me that a small group of dedicated professionals can achieve a lot, particularly in developing countries where the need for social services is immense, while a pool of well-trained practitioners is scarce. I am trying to use a similar approach in my research studies, not just collecting data in other countries, but also training and investing in local research teams and staff who, in the future, could conduct their own studies."

In 2009, she graduated from Columbia with a PhD in social work with a concentration in advanced clinical practice.

After holding research positions in the Global Health Research Center of Central Asia at Columbia and the Suubi (Hope) Projects for Care and Support for Orphaned Children in sub-Saharan Africa, she joined the faculty at SSA in 2012.

At SSA, she teaches a foundation course for students enrolled in the International Social Welfare Program of Study and in the Global Health Certificate Program offered by the interdisciplinary Graduate Program in Health Administration & Policy (GPHAP). The GPHAP program includes students from the University of Chicago’s five professional schools and is housed at SSA.

This course examines how global poverty, violence, social injustices, and health disparities are addressed in different nations and deepens students' understanding of global social and health problems and their potential solutions. Her other research course examines the principles, methods, and practices of evaluating social programs and services in the international settings. "This skill is particularly crucial for students pursuing a career in the field of international development as an increasing demand for transparency and accountability has heightened the need for evaluation of effectiveness and impact of programs."

A savings program organized among women in western Africa is helping raise the standard of living among some of the world’s poorest people by encouraging enterprise. A family coaching program is also helping families learn how to help their children, who are frequently sent away to work in gold mines, as housemaids, or other jobs away from home.

Her current project in Western Africa, "Evaluating Effects of Economic Strengthening and Child Protective Interventions among Ultra-poor Families in Burkina Faso" is a three-year study that is part of a cooperative agreement among the University of Chicago, Women's Refugee Commission, and Trickle Up, a not-for-profit agency based in New York City, and Burkina Faso. It is among the first studies using experimental design to test the impact of integrated psychosocial and economic-empowerment interventions on the child protection and mental health outcomes among families living in harsh economic conditions in developing countries.

Ismayilova is studying families who are part of a program operated by Trickle Up, which began working in Burkina Faso in 1986. Trickle Up also has projects elsewhere in Africa as well as India and Latin America, and works with people earning less than $1.90 a day, the World Bank's definition of extreme poverty. It has pioneered a program to "graduate" people out of extreme poverty and after two years become economically self-sufficient. The approach is often referred to as “economic strengthening," which provides access to riskfree capital, access to savings and credit, and skills training to confront extreme poverty. It uses savings groups for women as the key strategy.

While extreme poverty puts children and families at risk for poor outcomes, cultural norms and practices are believed to play roles as well. Therefore, this study looked at the impact of the economic program when delivered alone and in combination with a family counseling component. Economic intervention targeted only women, but this additional family component brought together all members of the household, including husbands, children, family patriarchs, and co-wives, because polygamous and multi-generational households are very common in rural Burkina Faso. Goals were to address normative beliefs related to protection of children from violence and exploitation, and to raise the awareness about the country-specific risks such as child labor, child separation, child marriage, girls' education, and religious schooling. The discussions were developed and led by coaches from the local community-based organization, ADEFAD (Aide aux Enfants et aux Familles Démunies or Help for Children and Poor Families), which has more than ten years' experience raising awareness around the rights of children in Burkina Faso.

During guided family discussions, coaches also pointed out the dangers of sending children away from home for work. Boys are often sent to work in gold mines, cotton fields, or cocoa plantations in the southern part of Burkina Faso, the Ivory Coast, or other neighboring countries. Many are enrolled in religious schools, where they are subject to hazardous unpaid work and corporal punishment.

Girls are sent to larger towns to be domestic servants. The family coaches also discussed the impact of forced marriage for girls and cultural attitudes that left girls vulnerable to violence.

As the study site, 12 pilot impoverished villages were selected in the Nord region, located in the semi-arid Sahel region near the border with Mali, characterized by extreme poverty and an ongoing food and nutrition crisis due to cyclical droughts. For the study, the team recruited mothers and children ages 10-15 from 360 ultra-poor households, defined as those who are among the poorest of the extreme poor. A third of the families received the economic strengthening program—savings groups for women (Trickle Up group); a third received family coaching on child protection issues plus economic strengthening (Trickle Up Plus group); and the last third were a control group on a waiting list to participate in Trickle Up activities.

"The use of randomized studies with control groups, an important way to evaluate and test evidence-based policies and programs, is still not very common in global development work. Using advanced research methods in developing and evaluating social interventions is even more important for low-income countries, where resources are limited and practitioners and governments should know and invest in programs that work," says Ismayilova.

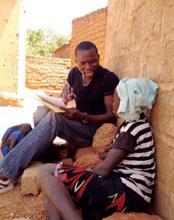

A team of graduate sociology and psychology students from the University of Ouagadougou, the main university in Burkina Faso, did the interviewing for the study. Ismayilova and other University of Chicago researchers trained the team, which obtained informed consent and administered the surveys.

The findings after the first year suggest that while family economic status and food security improved in both intervention groups, these economic gains reached children only in the Trickle Up Plus group that received the combined intervention. The effects were notable in the reduction of hunger among children as well as lower symptoms of depression and trauma and higher reports of self-esteem, particularly among younger children. In addition, mothers who participated in the combined intervention showed reduced use of harsh discipline methods, expressed more supportive child protection beliefs, and showed a better quality of child-parent relationships compared to women receiving the economic empowerment intervention alone.

Sometimes families/parents use food deprivation as a form of punishment for children, which can explain why reports of hunger among children were reduced in the group receiving economic intervention integrated with family counseling.

"The children in the Trickle Up Plus group get a voice in the family discussions, which improves their status with the family. In many societies, including in Western Africa, parents emphasize respect and unquestioning obedience to adults or elders over children's right to voice their opinion or concerns. In this study, we focused on child mental health and specifically on depression, trauma, and self-esteem because parents, especially when overwhelmed by chronic poverty and daily survival, underestimate the importance of emotional needs and children often suffer in silence," Ismayilova says.

In addition to the effects on children, we observed significant improvements for women, which is explored in a new paper by Ismayilova. Women receiving economic interventions (Trickle Up and Trickle Up Plus groups) reported better marital relations and reduction in emotional violence from their husbands. "In situations where the husband is excluded, spousal abuse can occur because the husband is resentful of his wife and her new role as a money earner," explains Ismayilova.

"But when the family has a chance to talk together as a group, the husband feels included," she adds. "We noticed that the men were very open when they were able to talk about how they feel. They said they appreciated the ability of their wives to contribute and didn’t feel like they were carrying the whole burden of providing for the family."

Women were a focus for an intervention that included efforts to improve incomes and to become more sensitive to the needs of children.

Alexice To-Camier, senior program officer at Trickle Up and former country director in Burkina Faso said the group was pleased that the intervention Ismayilova studied "translated into increased levels of self-confidence in mothers and their children as well as reduced levels of stress and anxiety. Some children no longer had to worry about being sent away from school because of unpaid school fees or feel ashamed because their parents were unable to buy them decent clothes or pay for school supplies," To-Camier says.

"Mothers of these children have had little to no formal education, one of the factors contributing to their condition of extreme poverty. Having a Trickle-Up field agent come to their home regularly to talk to them about issues relevant to their concerns about their children is something they found very valuable. They trusted the agents that talked with them because they were from their local community, To-Camier says.

"It will take longer to understand the impact of the intervention on early and forced marriages or other cultural practices. Some of the typical practices, such as girls being married early, have financial reasons but also are deeply culturally rooted and may take longer to change. Girls in our study are just entering that critical age when their marriage becomes a viable option for families, as well as for girls themselves, to reduce financial burdens on households and to secure the girls' future. We will continue following up with the children in this study to see if there are additional longer-term effects of the intervention," she adds.

The family component "is something that could be integrated into our economic strengthening program as the results point in the direction that working with families together and addressing non-economic factors are critical to improving the protective outcomes for children. We hope to share our learning from this research with other development organizations operating in the region," she adds.

> > > . < < <

UChicago students and a postdoctoral fellow joined Ismayilova in working on this study. "Leyla's study is implemented in a multicultural context, where numerous concepts such as the definition of 'household' and 'child exploitation' have to be made relevant to local context. I believe Leyla's study holds an outstanding potential to contribute to further discussion on how important concepts such as a child's well-being, hazardous labor, and child-parent relations are tested and contextualized to enable research that is not only robust but also culturally relevant and valid," says Leyla Karimli, a former postdoctoral fellow at NYU's McSilver Institute for Poverty Policy and Research is now an Assistant Professor of Social Welfare at the Luskin School of Public Affairs at the University of California at Los Angeles.

Karimli served as the study co-investigator and oversaw the development of the survey instrument related to household's economic well-being, women's economic empowerment, and child labor. "In 2014, Leyla and I traveled to Burkina Faso to train local research assistants and data collectors, pilot the study instruments, train staff on data management and statistical software, and hold extensive discussions with community collaborative board members, consisting of local university professors and child protection experts, to ensure that our study and measurement tools were relevant and sensitive to local cultural context," she adds.

The two learned of the importance of families in child welfare in such countries as Burkina Faso. In emerging economies, state-level child-protection institutions and mechanisms can be underdeveloped and, as a result, families and communities serve as vital and primary child-protection mechanisms.

An SSA master's student who worked with Ismayilova on the project was Eleni Gaveras, AM '16, who is currently pursuing a doctoral degree at the George Warren Brown School of Social Work at Washington University in St. Louis to become a researcher in global mental health. She assisted Ismayilova on data management, data analysis, and drafting manuscripts. At the International Organization for Migration, a United Nations organization, Gaveras had worked on access to health for undocumented persons, refugees, and mobile populations in Tanzania.

Gaveras said that international development efforts and economic empowerment programs frequently do not include intervention tools and strategies available to social workers that are known to improve child protection outcomes or reduce domestic violence. "This project assesses how additional psychosocial components for families might have deepened the effect of economic empowerment programs on child well-being. Moreover, the project looks at broader indicators of family well-being from a social work perspective that might be otherwise overlooked, especially in humanitarian emergency and low-resource settings, and are often limited to family income and poverty reduction."

Austin Blum, a third-year medical student at UChicago's Pritzker School of Medicine, worked on data analysis for the project. He investigated the prevalence of adverse and traumatic experiences among children in this study and analyzed the relationship between life stressors and children’s mental health outcomes.

"One insight from the project is that environmental stressors have a differential effect on children’s health and well-being in developing nations. As expected, children who reported experiencing violence and exploitation had worse outcomes. But other activities, such as working for a family business, showed a protective effect; that these children had more confidence and were less likely to have mental health difficulties than their peers. The implication appears to be that toxic stress in childhood, particularly when inflicted by exposure to chronic and severe maltreatment, adversely affects development. However, positive sources of stress may better prepare children to respond to life’s challenges, build their resilience, and socialize them into productive roles in adulthood.

"Professor Ismayilova has made a career of studying and improving child mental health in countries where poverty and other environmental stressors are at their most desperate. Her empirical approach to how social conditions shape individual health is classic University of Chicago," he says.

The study, "Evaluating Effects of Economic Strengthening and Child Protective Interventions Among Ultra-poor Families in Burkina Faso," was funded by the Children and Violence Evaluation Challenge Fund, a joint initiative funded by the Bernard van Leer Foundation, the Oak Foundation, the UBS Optimus Foundation, and an anonymous donor, and hosted by the Network of European Foundations (NEF) and co-funded by the Child Protection Working Group (The United Nations Children's Fund/UNICEF).