Teacher's Journey

Over his career, Stanley McCracken has connected research with practice to teach mental health and substance abuse treatment

By Jessica Reaves

VOLUME 20 | ISSUE 1 | WINTER 2013

SSA Senior Lecturer Stanley McCracken has taught and trained countless social workers, psychologists and psychiatrists during his 30-year tenure at SSA, both in the classrooms at the School and at nonprofit agencies and government departments across Illinois and beyond. As an expert in mental health and substance abuse treatment, he is known for his tremendous teaching skills and his approachable and gregarious manner.

ABSTRACT

An expert in mental health and substance abuse treatment, SSA Senior Lecturer Stanley McCracken has taught and trained countless social workers, psychologists and psychiatrists during his 30-year tenure at SSA, both at the School and at countless nonprofit agencies and government departments. Throughout his career, McCracken has been a powerful advocate in the movement to unite the frequently disparate worlds of research and practice, such as his deep knowledge of the latest thinking in treatment for dual disorders.

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

“He makes everyone feel comfortable, important and themselves,” says Deborah Jackson, the mental health program director at Asian Human Services in Chicago, where McCracken has consulted and trained for many years. “His relational skills make him real. He’s humble, kind and engaging. It’s exceptionally valuable to our multi-cultural staff and clients, who come from 55 different countries and speak more than 25 different languages.”

Throughout his career, McCracken has been a powerful advocate in the movement to unite the frequently disparate worlds of research and practice—how to immediately implement newly acquired information in a clinical setting. In fact, his biggest asset as an educator may be his deep understanding of the latest thinking in the field.

For example, McCracken continues to be at the forefront of changes in treatment for dual disorders, when a client has both substance abuse issues and mental illness, which he has been studying since the late 1970s, when he worked in the University of Chicago Department of Psychiatry. “I was curious about whether and how personality characteristics, mood, psychiatric symptoms, etc. might influence what drugs a person might choose to take,” he says.

Today, McCracken notes, primary care physicians are more likely to integrate treatment of mental illness, addiction and dual disorders into their practice. “There is also a greater emphasis on community-based services than there used to be, particularly for people with severe and persistent mental illnesses and addiction problems,” he says. “At the same time, there is increasing recognition that talk therapies, such as cognitive behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy, are as effective— or even more effective—than medication.”

McCracken’s journey from growing up in a small town to helping introduce new ideas such as these into social service programs across Chicago wasn’t a simple one. Those that have worked with him wouldn’t be surprised to hear about the twists and turns it has taken. In the end, however, those experiences have given McCracken the ideas, insights and capacities to become the teacher and connector he is today.

McCracken's social work career has included trips far and wide, including a 1996 visit to the Qigong Institute in Beijing.

Stan McCracken knew he wanted to teach at the college level from the time he was a teenager. He just didn’t know he wanted to teach social workers. “In high school, I wanted to be a biological oceanographer,” he says. “When I graduated in 1965, though, science was very much tied up in the military industrial complex.” When he was in high school in Hermiston, Oregon, that wouldn’t have been a problem. McCracken calls it “the brown part and the red part of the state,” referring to the area’s flora and to its politics. But McCracken’s path moved away from science and conservative politics.

So he chose to study English and Asian studies at Northwest Nazarene College. In 1969, after graduation, he intended to begin a master’s program in comparative drama. But when classifications were assigned for the selective service, McCracken was 1-A: “available for unrestricted military service.” “I knew then there wasn’t any way I was going to graduate school,” he says.

With his hope to work out a deferment to join the Peace Corps undone by a trick of timing, McCracken enlisted in the Army to study languages—stating a preference for Chinese, Japanese or Korean, figuring those languages might help keep him out of the ongoing war in Vietnam. But the Army had other plans.

After learning Vietnamese in the military’s language program, he spent a year in Vietnam working as an interpreter, with a brief interlude with Command Military Touring Shows, playing the bass in a band with other linguists: “Tran Hung Dao and the Ethnic Minority” toured South Vietnam with a repertoire of American songs. Before his tour ended, McCracken played in a second band, the Red Mud Boys, and music continues to play an important part in his life (he and his wife, Susan, had a wedding band called Wavelength, and he has played alongside many of his colleagues over the years).

After the military, McCracken began studying at Portland State University, reading “a lot of Asian philosophy and religion,” he recalls. “A lot of the books I was reading had introductions by Jung, so I moved from philosophy and religion and into psychology.”

About this time, McCracken began dating Susan, and after getting married on Mt. Hood, the couple moved to Chicago, where she had a full scholarship to study clinical psychology at DePaul University. He went to work at the VA and did some vocational testing. “I scored very high for either being a social worker or a priest. And given that I was already married, I didn’t think I was a likely candidate for the second option,” he says with a laugh.

He enrolled in SSA, where he found himself fascinated by his classes across campus in behavioral pharmacology. “I wondered, ‘Is anyone doing this stuff with people, instead of with pigeons and rats?’” They were, of course, just across the street in the University of Chicago’s department of psychiatry, where, as part of the Depression Study Group and the Drug Abuse Research Center (DARC), substance abuse research pioneers Bob Schuster, E.H. Uhlenhuth, Chris-Ellyn Johanson and Marian Fischman were conducting drug studies.

As it happened, Uhlenhuth and Fischman had a role for McCracken in their work, providing psychotherapy to people in the drug studies. When he graduated SSA, they hired him, and his work expanded to conducting diagnostic evaluations, diagnosing using Research Diagnostic Criteria and providing services based on empirically supported interventions. He also began working with federal offenders receiving methadone treatment in the Drug Abuse Rehabilitation Program, and interventions for use in conjunction with treatment for medical problems and illnesses, including cancer, gastrointestinal disease and diabetes.

Harriet de Wit met McCracken during this time, when they were both working in the behavioral pharmacology group. Now a professor in the University of Chicago’s Department of Psychiatry, she recalls his accessibility and his ability to bridge the clinical aspect of his work to fully engage with people. “Despite using the relatively impersonal, strictly behavioral approach that was popular at the time,” de Wit says, “Stan had an extraordinary rapport with patients as well as with research volunteers, and always treated them with the greatest respect and with a ready and warm sense of humor.”

It was during this work that McCracken began to develop his strong belief that the long-standing separations between clinical work and research could—and should—be eliminated. “Because I learned to practice this way at SSA,” McCracken wrote in a recent teaching statement, “I have never seen a gap between research and practice, though I learned that many do.”

In 1980, McCracken began the doctoral program at SSA. He continued to work full time in the psychiatry department, and took a number of classes at the medical school. Three years later, McCracken, who had done some guest lecturing in the adult psychopathology course at SSA, was asked to take over the class. He did so happily, launching his teaching career.

McCracken soon moved to the non-tenure track. He wanted to take what he’d learned beyond the boundaries of academic life. “My interests were much more with practice and teaching than research,” McCracken says. Although he has focused on bringing the lessons of research into practice over his career, he has also worked to take what he’s learned in the field back to the academy as well. He has published a number of articles and book chapters covering issues from behavioral medicine to psychiatric rehabilitation to evidence-based practice, and he is co-author of two books, Practice Guidelines for Extended Psychiatric Dare: From Chaos to Collaboration and Interactive Staff Training: Rehabilitation Teams that Work.

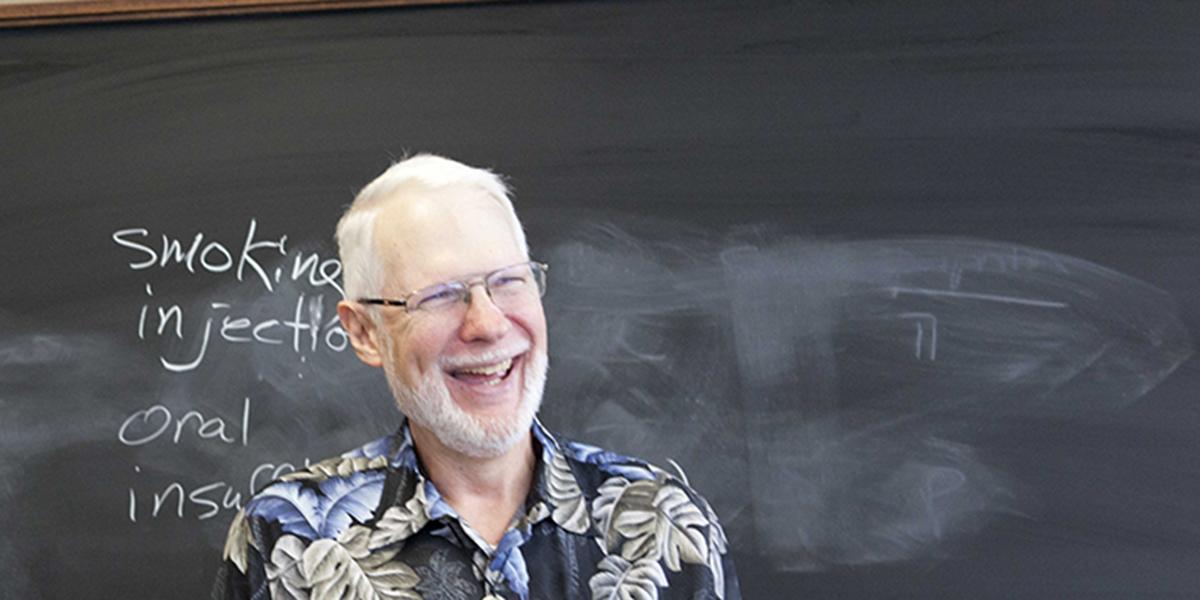

McCracken today, in front of his cozy office at SSA.

In 1992, McCracken had transferred from the Outpatient Psychiatry Department to what is now known as the University of Chicago Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, where he’d planned to concentrate on a program for treating dual disorders. Instead, the Illinois Department of Mental Health asked him to provide training for staff at all state-operated psychiatric hospitals, an opportunity that opened up another door in his career.

McCracken and the staff began by training internal and external staff through a series of psychiatric rounds, individual and group supervision of students and staff, and training seminars. Eventually, he and Patrick Corrigan, a professor of psychology at the Illinois Institute of Technology and an expert in psychiatric rehabilitation and mental illness stigma, developed Interaction Staff Training, which combines organizational and educational approaches.

Requests for training and collaborative training began to pour in; the Illinois Department of Alcohol and Substance Abuse, the Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services, and the Illinois Department of Rehabilitative Services all contracted McCracken to help to create training programs. McCracken also coordinated with Annette Backs, now assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatric Rehabilitation at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, to develop a four-semester program to train psychiatric rehabilitation counselors in Illinois community colleges, a blueprint that was eventually exported to Texas, Florida, Michigan and Singapore.

Over the years, McCracken has also helped develop staff training curricula in substance abuse and long-term care, as well as a program to train Iraqi primary care physicians and community mental health workers to provide services to survivors of torture. He has worked for the Veterans Administration, the Department of Justice and a number of other states, as well.

“He teaches people to think, how to search for information, how to evaluate that information, and then rethink. He’s strong in promoting evidence-based practice but isn’t stuck in his ivory tower, and he understands the value of practice-based evidence. He’s improved the skills of paraprofessionals with his psychosocial rehabilitation program, and encouraging professionals to work cross-culturally in order to respond to a multicultural, multilingual population,” says Mary Lynn Everson, the senior director of the Heartland Alliance Marjorie Kovler Center.

Everson began working with McCracken nearly 20 years ago, when Heartland Alliance for Human Needs & Human Rights asked him to train its mental health staff. He has worked with her since on the establishment of the Heartland Training Center, a program offering training and consultation in integrated mental health and substance use treatment, case management and cultural competence.

“He’s a lovely man, so generous with his time, so very willing to share his knowledge but also encouraging sharing of information between others in his network,” Everson says. “And frankly, I can’t wait to see what Hawaiian shirt or Panama hat he’ll have on next!”

These days, McCracken’s mornings are reserved for bicycle rides with Susan, an adjunct faculty member at SSA who also has a private practice in Des Plaines. “Susan and I do occasionally discuss social work/psychology issues at home, and the conversation goes both ways,” he says. “Sometimes it is more about just formulating ideas and saying them aloud; other times it is getting suggestions and consultation.”

His schedule remains busy and challenging. Last summer, he updated a review on literature on schizophrenia in older adults, and returned to an old passion: studying spirituality and religion in social work practice. “I also spend quite a bit of time with community programs,” he says. “And I seem to be supervising a lot of former students. There’s a guy in Japan, someone in Anchorage, and another one [who until recently was based] in Thailand. Skype and I are good friends.”

McCracken is also fascinated by the issues presented by the aging Baby Boomer generation, including dementias, which promise to attract even more attention as the population ages. “The literature on dementia is evolving incredibly quickly,” he says.

As excited and energized as he is about new and emerging theories of social work, McCracken’s greatest passion is reserved for teaching. “I have an immense respect for people who go into this field, the students and practitioners,” he says. “I want to do what I can to help people provide services, to serve the population. I think of this like a calling, as a priest might.”

Abby Erikson, a senior technical advisor with the International Rescue Committee in Washington, D.C., can attest to this. Since graduating from SSA, she’s worked in refugee camps around the world to develop programs for responding to violence against women and girls. McCracken was her professor at SSA and has been her clinical supervisor for the past several years. During that time, she says he’s been a teacher, mentor and advisor, and that his influence on her professional development has been invaluable.

“Stan has had a tremendous impact on my ability to translate learning into practice, with an emphasis on understanding the human condition and experience across cultures,” Erikson says. “My work has been intense and filled with difficult-to-navigate cultural terrain. He’s provided a safe space for me to explore the challenges of working in that environment and helped me to constantly evaluate and assess my assumptions and understanding of clinical care and social work across cultural settings.

“His sense of humor and humility have allowed me the room to make mistakes, ask questions, share my experiences and partner with him to become a better social worker. Stan has played a vital role in [shaping] the practitioner—and person— that I’ve become,” Erikson says.

Throughout the SSA network, and around the world, there are doubtless hundreds, even thousands, of students, clinicians and social service providers who are as grateful.

Stan McCracken acknowledges the breadth of his influence in a slightly different—and entirely characteristic—manner. “Next year it will be 30 years that I’ve taught at SSA,” he says, with just a hint of wistfulness. “Almost every year a student comes up to me and says, ‘My mom or my dad had you as a teacher.’

“I haven’t had anyone reference a grandparent,” he adds with a broad grin. “Not yet, anyway.”