A Career Focused on Urban Education and Social Justice

The work of Charles Payne connects research with the community.

By Charles Whitaker

VOLUME 24 | ISSUE 2 | SUMMER 2017

In the late 1960s, Charles Payne, the Frank P. Hixon Distinguished Service Professor at SSA, was among a group of Syracuse University undergraduates recruited by its School of Education for an initiative designed to reform a failing elementary school that served a nearby public housing project.

ABSTRACT

Among the stellar faculty members at SSA is Charles Payne, the Frank P. Hixon Distinguished Service Professor, who is retiring and taking on a new challenge in Newark, New Jersey. During his career, Payne has blended influential scholarship, community activism, and public service with exceptional teaching. He is the author of a number of influential books. Payne has spent the bulk of his career in Chicago, where he has conducted research and worked on education and community development issues on both the West and South Sides. He is also one of the founders of the Education Liberation Network, a national coalition of teachers, community activists, researchers, youth and parents, devoted to empowering young people—particularly low-income youth of color—to be agents of their own success.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

t was, recalls Payne, a well-intentioned, if hapless, effort. "The folks at Syracuse were way out of their element," he says. "They had no conception of how to do that kind of work."

Still, for Payne, who was dispatched to help in a sixth grade classroom, the experience was transformative, although the children could be unruly and impertinent in ways that astonished him. "I had grown up in a rural area where black children did not speak back to adults. So to go to work with children from the Syracuse housing projects...that was a whole new culture for me," he says. He was exposed in that classroom to the power that education has to change the lives and trajectories of urban children and the communities in which they lived.

"I was interested in community organizing," he says. "I always wanted to work on urban issues. So I began to see education as a useful framework to look at and think about the issues facing black America.”

And so, in 1970, after earning a bachelor’s degree in Afro-American studies from Syracuse (he was one of the first people in the country to earn a degree in that discipline), Payne embarked on a 40-year career focused, in large measure, on the role of education as a catalyst for change in black communities.

The 1970s were a nascent time in the development of African American studies at most white institutions. He had no clear idea of what he wanted to do post college. “I never thought of African American studies as a career; in fact, at that point, it wasn’t really possible to think of it as a career,” he says. He headed to Northwestern’s doctoral program in sociology "because sociology is where you went if you wanted to work on urban issues."

After completing his PhD, his rise up the academic ranks took him from Southern University in Baton Rouge, LA, to Williams College, back to Northwestern, then to Duke and ultimately to the University of Chicago and SSA, where he also is an affiliate of the Urban Education Institute and an affiliate of the Center for the Study of Race, Politics, and Culture. Along his academic career path he built a formidable reputation as a scholar who also rolled up his sleeves and dove into community activism. "Long before researcher-practice partnership became a buzzword, Professor Payne was modeling how to bring community members into the research equation in an authentic way," says his former student Eric Brown, AM '08, who says he would like his own work to mirror that of his mentor's. Brown is a doctoral student in the Program in Human Development and Social Policy at Northwestern University.

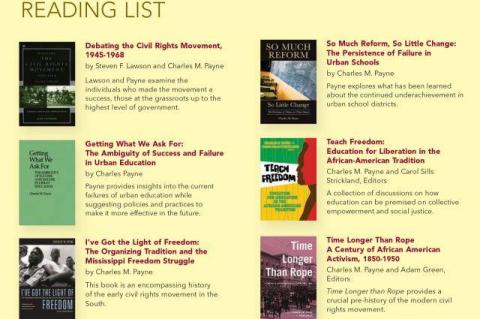

During his career, Payne has adroitly blended influential scholarship, community activism, and public service, with a stellar teaching career that has earned him accolades and a devoted following of former students. His seminal books, including Getting What We Ask For: The Ambiguity of Success and Failure in Urban Education (1984) and So Much Reform, So Little Change: The Persistence of Failure in Urban Schools (2008), have attempted to chronicle and unpack what researchers and practitioners have learned from three decades of efforts to rehabilitate inner city schools. He is also the author of I've Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle (1995). The book won awards from the Southern Regional Council, Choice Magazine, the Simon Wiesenthal Center, and the Gustavus Myers Center for the Study of Bigotry of Human Rights in North America.

In the decades between those publications, he's seen hopeful signs of improvement in urban school districts, despite the grim headlines. “If you go back to the early 2000s and compare that to now, a lot of things have absolutely gotten better,” he says. “The quality of leadership in urban systems is probably better. The degree to which we use data is absolutely better. And, overall, over the last decade, urban students have closed the test score gap with the nation by about a third. There’s still a big gap, but American urban schools have been making progress.”

Payne is heartened by some of the signs of progress he’s read about, like the fact that over the past 10 years the Chicago Public Schools (CPS) is one of the two or three fastest improving districts in the country, according to the National Assessment of Educational Progress.

But he says most people are profoundly unaware of the progress being made in urban schools. He attributes that partly to the misinterpretation of the plethora of studies that show a correlation between economic status and race on the one hand and academic achievement on the other.

"A lot of these studies confuse what is possible academically for urban children with what is typical," he says. "Beyond that, we have all been conditioned to expect failure for black and brown children. But one of the things I'm arguing in my current work is that we've really been barking up the wrong tree. The question which has been driving this debate is: Why have poor children and children of color failed? We should go at it the other way around. We should be looking at where they have succeeded and how we can build on that."

Some of the most successful cities are places that invest more in shaping positive organizational cultures, which includes investing in leadership. Some of them are places that redirect traditional flows of resources and institutionalize higher expectations for everyone, explains Payne. In Chicago, where Payne has spent the bulk of his career, he has conducted research and worked on education and community development issues on both the West and South Sides. He also is one of the founders of the Education Liberation Network, a national coalition of teachers, community activists, researchers, youth, and parents, devoted to empowering young people—particularly low-income youth of color—to be agents of their own success. Payne's work in the field and in the academy stands as a model of engaged research, where scholars and community members come together as equal partners in the crusade to shepherd the children in impoverished black and brown neighborhoods to better outcomes in education and life.

"Charles has been a clear leader in the kind of school reform that is structured around grass roots parent-centric organizing," says Terry Mazany, president and CEO of the Chicago Community Trust, who, as interim CEO of Chicago Public Schools in 2011, tapped Payne to be his chief education officer. "He understands how to take quantitative and qualitative research and transfer that into a model that supports whole-school change from the bottom up."

It is a model that he will employ in his next venture. In June, he retires from SSA and will take up residence at Rutgers University in his home state of New Jersey. There, he will direct an initiative in which education, civic, and business leaders in the city of Newark forge partnerships to improve the quality of life for Newark's most vulnerable children and families. Some aspects of that work are likely to be similar to the program Payne helped institute eight years ago during his two and half year stint as acting executive director of the Woodlawn Children's Promise Community in Chicago. Modeled on the Harlem Children's Zone in New York, the Woodlawn Children's Promise Community is a partnership between community leaders and residents of the Woodlawn neighborhood, CPS, and scholars and administrators from the University of Chicago who developed a program that attempts to provide "cradle to young adulthood" support in an effort to impact everything from early childhood development and healthcare to curbing the rampant violence that plagued the community.

Though he had long been a proponent of this kind of community engagement, Payne says overseeing the Woodlawn Children's Promise Zone and watching legions of "promise children" come into their own has been one of the highlights of his career. "That was a really generative experience for me," he says. "It was really important work, and it's the work I want to build on at this stage in my career. I'm not interested in doing what most public schools do or what most charter schools do. I want to build on the community school model, but also create programs that jack up the academics to a really high level while emphasizing social service—the idea that you can make a difference in your school, in your family, in your community."

His commitment to teaching and social justice is rooted in his upbringing. He was raised in Woodbine, NJ, in the southern tip of the state. He is the oldest of four children. His mother was a seamstress who worked at the local garment factory sewing the sleeves on military uniforms; his father worked for a small, black insurance company and tended bar, "which means he literally knew everybody in a two or three county area, because either you have insurance or you drink."

Payne says the storytelling tradition that animated the conversations he was exposed to as a child—at home, at church, and at the elbow of his maternal grandfather—helped shape his classroom performance style later on. "I'm not that great a speaker," he says. "But I grew up in a black Pentecostal tradition, which is a strong narrative tradition, a strong musical tradition. I do think some of that tradition comes through in the way I teach and write.”

He also was influenced by a pair of aunts, both teachers, who from an early age plied him with books and insisted that he go to college. Early on, he thought he would be a history teacher, but at Syracuse, he was allowed to design his own major. He chose African American studies. “This was the madness of the 60s,” he says. “When they told me I could make up my own major, I chose Afro-American studies. I had been exposed to so little of that material before college, once I started reading it, I just couldn't stop."

Charles Payne, teaching one of his many popular courses at SSA.

Making a difference has been an essential element of Payne’s own teaching career, including his nearly 10 years at SSA. And though he is known as a hard-to-please taskmaster, he has also cultivated a vast network of admiring former students who say he is generous with his time and counsel inside of the classroom and beyond.

“The thing about Professor Payne is that he is a really tough grader, more so a tough critic,” says Eric Brown, who took two classes with Payne during his time in SSA. “You would hand him a 25-page paper and you’d get it back with all sorts of writing on it. It might have writing in different colors, like he went over it one time and then went over it again because he felt he didn’t critique it enough the first time. But as a teacher and a mentor, he was like an authoritative parent. He could be tough on me because he knew that’s what I needed and that I could take it. But he has always made himself available when I needed him.”

Payne says he developed his taskmaster persona partly because he felt he had learned the most from his most demanding professor. Then, too, he was teaching African American studies when it was still being was dismissed in some academic circles, so he heaped on piles of reading and assiduously pored over the papers students submitted. “What you learn really quickly at these elite liberal arts colleges is that many of the students—and some of the facult —have no respect for African American studies,” he says. “The thought is that if it’s African American, that means low academic standards, so it became very clear to me that the way you earn your place is with high standards. You want them in the lunchroom saying, ‘I don’t have time to do organic chemistry because of all this work in African American studies!’ At that point, you have a certain legitimacy.”

But even with the crushing workload and withering critiques, Payne’s disciples heap praise on him as a skillful moderator of classroom discussion. His specialty is facilitating difficult conversations about race and privilege. His “Social Meaning of Race” class was a particular favorite among SSA students. Benjamin McKay, AM ’10, who now works as dean of students at CPS’s Lakeview High School, recalls that his first assignment was to read playwright Lorraine Hansberry’s The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window, a meditation on race and politics—both sexual and civic.

“I walked into the class not knowing what to expect,” McKay says of that first session. “Professor Payne had us read lines from the play, some of which are pretty explosive commentaries about race and white bourgeoisie privilege. But doing that helped us understand how to talk about those things and not talk around them. Professor Payne was able to hold those discussions about these charged topics in ways that I had never experienced before and haven’t experienced since.”

Much of the magic, Payne says, is in the material he presents and not so much in his delivery. “The stuff that I teach—stuff about the civil rights movement and race and privilege—there’s just a certain power to it,” he says. “It’s hard to teach it really badly. It can be done, but it’s hard.”

“When things are going well you can see people growing,” he says. “You can literally see the lightbulb go off, and they will tell you, ‘damn, I never thought about that.’ That’s a significant payoff.”

As Payne prepares to leave Chicago and assume a new role in Newark, he worries that he won’t find his way back into a classroom any time soon. But he is looking forward to returning to his home state and once again putting into practice on a large scale the principles he has preached and modeled in smaller settings. There are big questions to be answered, such as: What kind of research can help make life in a metropolitan area better? And what are the demonstration projects that we can do that will help most? But he says there are people involved in this initiative who are deeply committed to the idea that they are going to be a part of the resurrection of Newark. “And my job,” he says, “is to figure out how to be a positive part of that change.”